Maxime Du Camp, The Convulsions of Paris

Du Camp, a writer and friend of the novelist Flaubert, presented a very negative view of the Commune in a four-volume attack. Here is an excert"

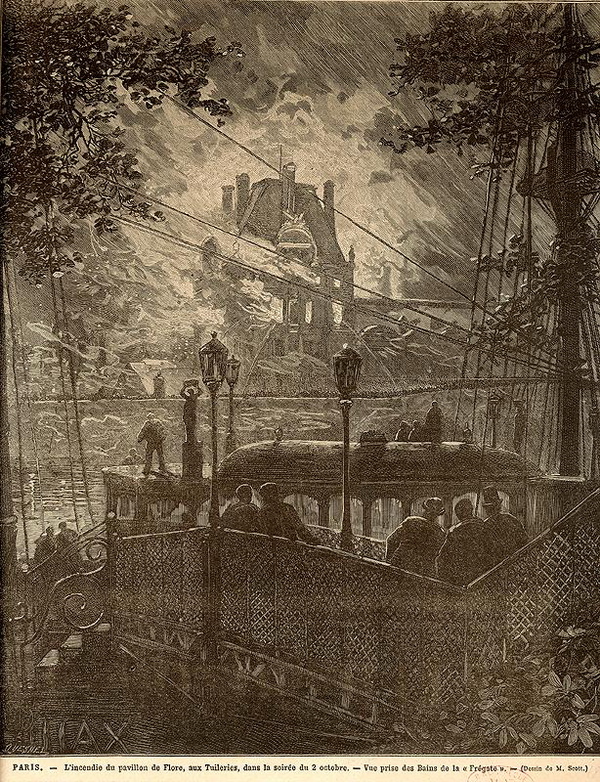

“O Paris, which is no longer Paris, but a cave full of ferocious beasts!” says M. Daubray’s harangue in “Satyre Ménippée.” Who among us did not repeat this  exclamationduring the terrible days of May 25-26? Everything was on fire; everything was going to be set on fire. An ocean of flame rolled over the city. Never was a battle so fierce, never had such destruction been seen. The storehouses of the Quai Bourbon were on fire, as well as the warehouses of La Villette and, in the same place, the depot of the Compagnie des Petites Voitures where, in preparation for the siege, piles of supplies were still to be found. Seven hundred and seventy two houses in flames, seven hundred and fifty four others attacked by fire; the d'Orsay barracks, the Tuileries, the Palais-Royal, the Cour des Comptes and its archives, the palace of the Legion of Honor, the savings banks, the Palace of Justice, the prefecture of police, the Gobelins, the Hôtel-de-Ville, the customs offices, the public assistance building, the Théâtre Lyrique, the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin, the Théâtre des Délassements-Comiques, the library of the Louvre, the ministry of finance, everything was on fire and collapsing, turning Paris into a horrific inferno. More than one Parisian, upon contemplating this spectacle, cried and asked himself, without daring to respond, if he truly belonged to the race and the country of the men who had committed this crime.

exclamationduring the terrible days of May 25-26? Everything was on fire; everything was going to be set on fire. An ocean of flame rolled over the city. Never was a battle so fierce, never had such destruction been seen. The storehouses of the Quai Bourbon were on fire, as well as the warehouses of La Villette and, in the same place, the depot of the Compagnie des Petites Voitures where, in preparation for the siege, piles of supplies were still to be found. Seven hundred and seventy two houses in flames, seven hundred and fifty four others attacked by fire; the d'Orsay barracks, the Tuileries, the Palais-Royal, the Cour des Comptes and its archives, the palace of the Legion of Honor, the savings banks, the Palace of Justice, the prefecture of police, the Gobelins, the Hôtel-de-Ville, the customs offices, the public assistance building, the Théâtre Lyrique, the Théâtre de la Porte-Saint-Martin, the Théâtre des Délassements-Comiques, the library of the Louvre, the ministry of finance, everything was on fire and collapsing, turning Paris into a horrific inferno. More than one Parisian, upon contemplating this spectacle, cried and asked himself, without daring to respond, if he truly belonged to the race and the country of the men who had committed this crime.

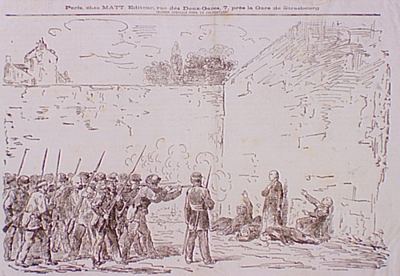

The French troops, in their turn intoxicated and maddened, charged into battle in a rage. During the first two days of the fight, May 22 and May 23, they had been calm, passively following their officers, who set an example and delivered this difficult street combat with abnegation, a form more unpleasant and painful than any other. The sight of the first fires filled them with anger; the resistance of the rebels exasperated them, and it was no longer possible to moderate them. Bad memories turned bitter in the hearts of the soldiers. These men, who had suffered so much, who had pointlessly expended so much bravery, who had put up with captivity, poverty, hunger, illness, longs stages on inhospitable roads and the shame of an undeserved defeat and who, as a reward for their humble sacrifices, had received nothing but insults, became the champions of theirpersonal cause. They had to reduce those who rebelled, those who set our monuments on fire, pulled own our military trophies, assassinated the country’s most honest men. What had these men they were fighting done during the war? They had drunk themselves silly amidst barrels of wine and eau-de-vie; perorated in the cabarets; neutralized the defense by their sacrilegious riots; had never gone out to meet the enemy and miserably husbanded all their forces in order to attempt to overwhelm France’s army and government. These soldiers, who had been accused of cowardice, who had been blithely called capitulators, instinctively understood that they were in the presence of men who by their lack of discipline, their unbearable braggadocio, their will not to fight, had been the surest auxiliaries of the invading armies. In striking them they thought they were not only obeying the law, but avenging the fatherland.

In reality, what they ruthlessly punished was less the murderous army of March 18 than the army which during the siege had systematically held itself back from its duty and from danger. It was this above all that gave a character of implacable brutality to the fight. The revolt had been without pity; the repression was merciless. As in battles that are prolonged beyond human strength, the intoxication of butchery seized all involved. Victors and vanquished had no forgiveness for each other. The laws of blood promulgated and applied by the Commune fell back on it. It was to be murdered in its turn.

In reality, what they ruthlessly punished was less the murderous army of March 18 than the army which during the siege had systematically held itself back from its duty and from danger. It was this above all that gave a character of implacable brutality to the fight. The revolt had been without pity; the repression was merciless. As in battles that are prolonged beyond human strength, the intoxication of butchery seized all involved. Victors and vanquished had no forgiveness for each other. The laws of blood promulgated and applied by the Commune fell back on it. It was to be murdered in its turn.

Was the illusion sincere on the part of the leaders of the insurrection? Did they think that, repudiated by the entire country, attacked by the French army, threatened by the German troops who would have forced their entry into Paris if the legal government hadn’t decided to act; did they think that their cause, without either a banner or a principle or a name could triumph and wasn’t condemned to a violent death? We are led to believe this is the case if we refer to certain documents of the era. On May 24, the very day when the murder of the hostages destroyed any chance of reconciliation, a proclamation was posted that members of the Central Committee had written the previous day. One could read with amazement the conditions proposed as if from one power to another: 1- The National Assembly, whose role has been terminated, must dissolve itself. 2- The Commune will also dissolve itself 3- The so-called regular army will leave Paris and hold itself at a distance of 25 kilometers. You would think you were dreaming! If a few men whose brains were absolutely perverted by the strange role they'd wrested from events were able to imagine that definitive victory was theirs, such was not the case for the consternated spectators of that descent of the revolutionary Courtille.[1] No one in Paris believed in the durability of this abjectly materialist power, and among those who had the singular courage to exercise it no one had any hope after May 25. Even if one was lacking in wisdom and patriotism, the most simple reasoning demanded that they put down their arms and that, for a cause all the more lost because it wasn’t born viable, they not sacrifice thousands of existences. This was what humanity demanded; but it was passion that carried the day, and all was lost...

The Burning of Tuilleries Palace